Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Wallpaper magazine

Text by Deyan Sudjic

Somewhere on the steppes of Central Asia, midway between Europe and China, is the city of Tashkent. Invaded by successives waves of Arabs and Persians, sacked by Genghis Khan in 1219, and colonised by the Russian Empire in 1865, the Silk Road hub has been home to Kazakhs, Tajiks, Turkmen, both Bukharan and Ashkenazi Jews, Koreans, Ukranians, Poles, Tartars, ethnic Germans and Japanese prisoners of War, finally becoming the capital of an Independent Uzbekistan after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

A country’s identity is usually shaped by the same fundamentals that more or less endure: language, heroes and myths, architecture, food, dress and religion. But in the case of Uzbekistan, the ingredients have demanded constant recalibration through the centuries. In Tashkent, now a city of 2.5 million, this is most apparent in the built environment: here you can find traces of at least five different cities and five different architectural cultures, the oldest being an ancient Islamic walled settlement, followed by an adjacient Imperial Russian colonial city, with a later Stalinist overlay. Today’s Tashkent is busy erasing the traces of a second wave of soviet architecture with gleaming white marble buildings that make it look like one of the more conservative Gulf states. Its sadly lifeless attempts to evoke the domes, colonnades and embellishments of Uzbekistan’s Islamic heritage camouflage everything from overwrough supermarkets to dull convention centres.

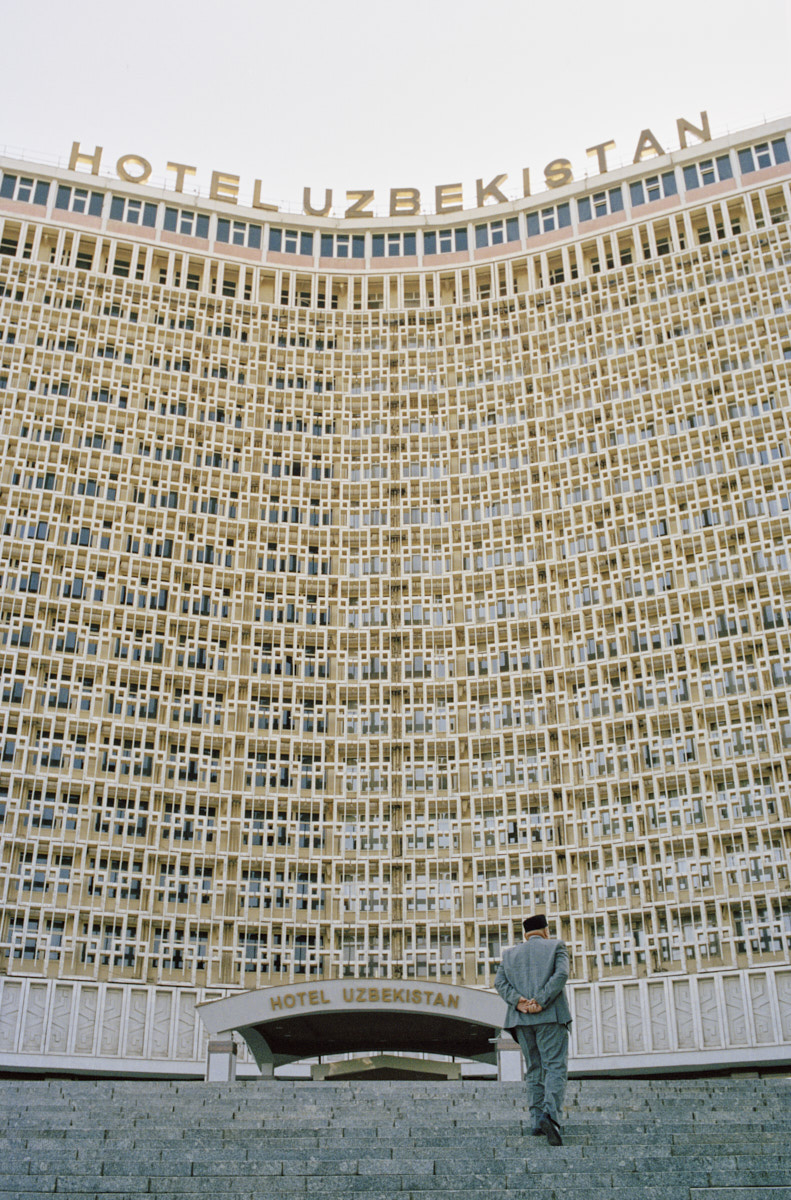

This retrograde modernising spree is wiping out the achievements of one of the most intriguing architectural experiments of the 1960s and 1970s, when the Soviet Union set out to build a Marxist-Lenininst Brasilia in Central Asia. Some of its highlights remain as prominent landmarks, such as the 1974 Hotel Uzbekistan, one of the outstanding monuments of Soviet modernism. In the delirious days of the early 1970s, when cultural freedom seemed a real possibility, and Tashkent hosted an annual international film festival, the hotel accomodated filmakers from all over the world in relative luxury. There was even talk of dissident directors introducing previously outlawed themes of colonial repression and gay relationships in their films at the festival. Today the property’s empty Vienna Café serves local beer in litre glasses to a few bored-looking indian teenagers.

Some of the energy of Tashkent in its days as an experimental cultural centre is still visible at the Ilkhom, a radical theatre started by the director Mark Weil in 1976, and which has thankfully survived his senseless murder in 2007. Like the nearby Navoi Cinema Palace, with its monumental concrete auditorium, its architecture represents the most creative period of Soviet modernism. The concrete is cracking, the fountains have been switched off, but the quality of the orignial architectural ideas is still clearly visible.

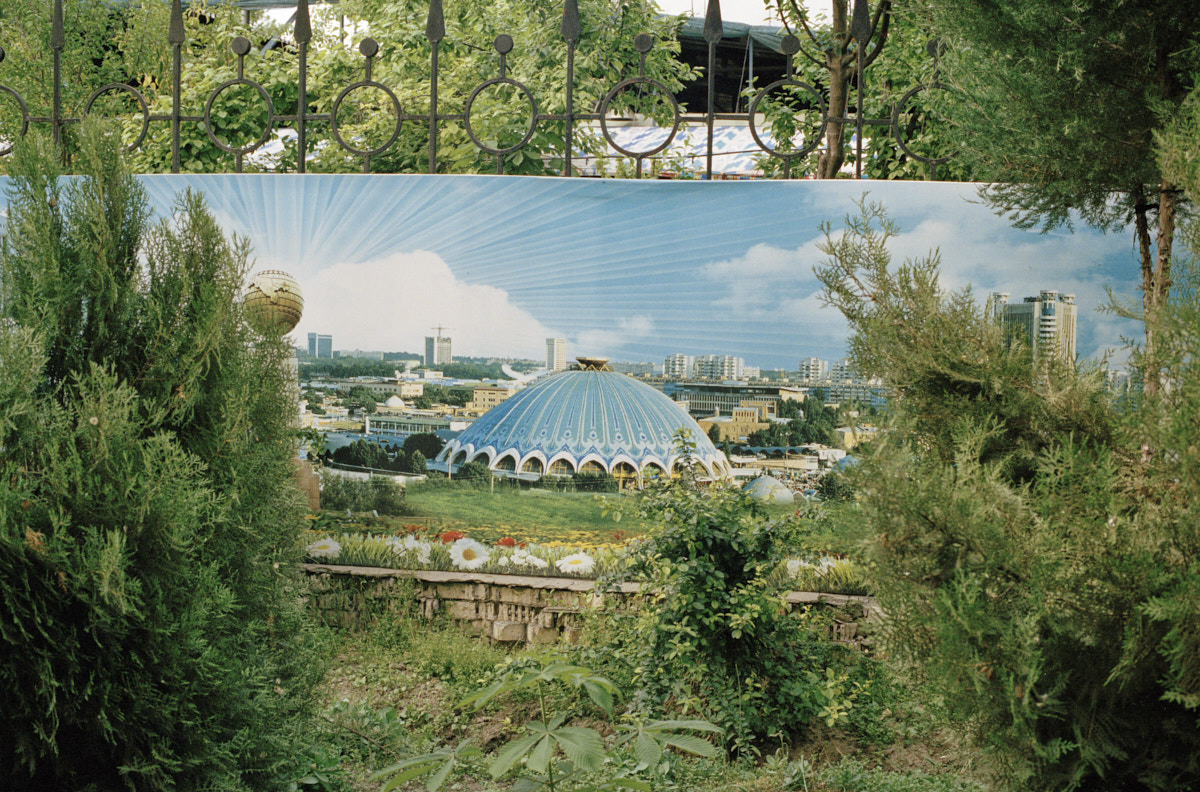

But many equally impressive monuments have been demolished. The Rossiya Hotel has gone, turned into a lumpen Grand Mir, and the Moskva Hotel seems unlikely to survive. Designed by Vladimir Spivak, the Moskva opened in 1983. It has 24 floors, which makes it a high-rise by Tashkent standards. The triangular floor plan is framed by three circular domed turrets, which have an impressive view of the dome of Chorsu Bazaar, Tashkent’s famous turquoise-tiled, flying-saucer market hall designed in 1980 by Vladimir Azimov and Sabir Adylov. In the summer of 2019 the Uzbek government confiscated the remains of the hotel from a Turkish developer, allegedly in default on his contract to restore the building, and began to look for a new owner. The decaying hulk of the tower has since disappeared behind a giant advertising hoarding.

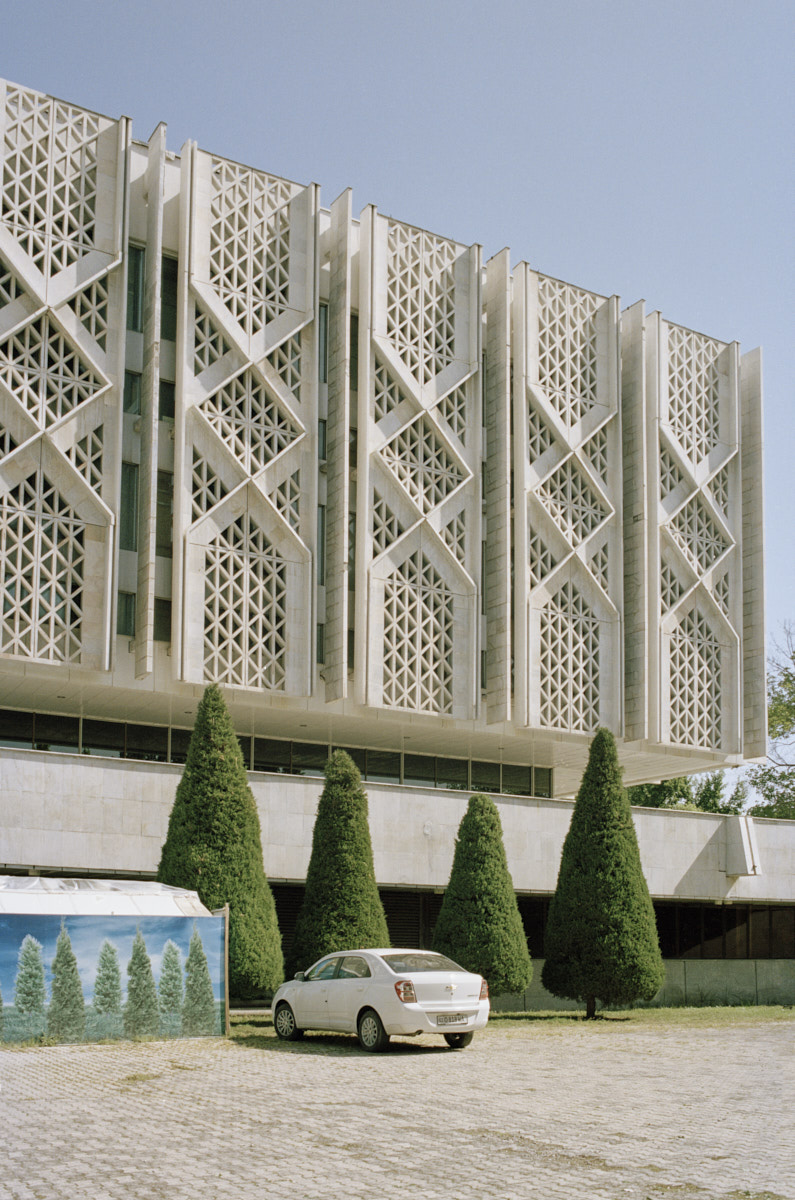

Tashkent’s once heroic government centre has been compromised beyond recognition. It was originally designed in Moscow by Boris Mezentsev, an architect who successfully made the challenging transition from working for Stalin to meeting the very different demands of the Khrushchev Brezhnev eras. Mezentsev’s House of the Ministers was an endless slab stretching apparently to infinity, hoisted up off the ground and floating on V-shaped concrete columns to form one side of the vast Lenin Square. The entire area has been comprehensively rebuilt since independance. Mezentsev‘s architecture has vanished under a layer of orange mirror glas and white marble.

Even the Uzbek language has not remained entirely constant. It was written in Arabic for centuries. Switched briefly to a Latin-based alphabet in 1928, before Stalin liquidated the burgeois nationalist intelligentsia an imposed Cyrillic on the Uzbeks on a fit of Russian Chauvinism ( he also tried to ban the veil). A newly independent country reverted to Latin script, though in Tashkent to this day you can still see signs written in Cyrillic - confusingly in both Russia and Uzbek. Uzbek cuisine, meanwhile, remains defiantly challenging; the Hyatt Regency's restaurant offers hand-spun noodles garnished with boiled horsemeat as a signature dish.

Faced with the impossible paradox of justifying the rule of a supposedly anti-imperialist USSR over Uzbekistan, a colonial relic of Imperial Russia, Soviet propagandists seized on the 15th-century poet Alisher Navoi as the figure on which to build an appropriate national foundation myth for their Uzbek subjects. Though Navoi

came from an aristocratic family and was born in Afghanistan, Moscow turned him into a prototype proletarian icon for Uzbekistan. He was celebrated as a literary genius to match Shakespeare and Dante, and as a compassionate visionary who had predicted the coming of a socialist Uzbek nation. Almost everything of cultural significance in Tashkent is named after him, including the opera house and the city's main boulevard. A post-Soviet Uzbekistan has added Tamerlane

(Christopher Marlowe's Tamburlaine the Great) to the national pantheon. Despite his genocidal tendencies, he is commemorated wit an equestrian statue that stands in front of the Hotel Uzbekistan, on the same spot once occupied by the busts of Karl Marx, Joseph Stalin and the first imperial Russian governor, Konstantin von Kaufmann.

A close reading of Tashkent's metro system tells you need to know about the city's complex identity. It started runnin in the 1970s, but seems much older. Independence Square station, for example, feels eerily like a transplant from the Moscow of the 1930s, even though it opened in 1977. It stands next to what was once

Lenin Square, from which Lenin's bronze statue has been deported. The marble plinth that once made it taller than a ten-storey buildin survives, now topped by a golden globe and a map of Uzbekistan. At its base is an exceptionally incompetent representation of a Madonn and child. The station's exterior is a peach-coloured marble slab, with a massive bas-relief bronze screen that depicts joyous Uzbeks waving their karnays, the 10ft-long brass ceremonial trumpets tha are to Uzbekistan what bagpipes are to Scotland, over their heads, flanked by clusters of dancing maidens and flag-waving citizens.

Once you have negotiated the uniformed ticket sales team (admission 1,200 soms, around ten British pence), you find ornate white marbl columns, a dazzling array of chandeliers, and trains that closely resemble enlarged versions of those boxy tin toys, printed a fraction out of register, that encapsulated Soviet childhood.

Elsewhere on the line you can find a station that used to be named after Maxim Gorky, Stalin's favourite novelist, but is now called Buyuk Ipak Yuli, or Great Silk Road. Not all traces of the city's Russian ascendancy have faded (20 per cent of the population are still ethnic Russians): the cafés serve a range of vodkas; the most popular ice cream parlour is still called the Moscow; and for some reason there is a brisk demand for Russian-language businesses offering walk-in polygraph services. Pushkin is still hanging on at a station further down the line. But two stations named after Uzbek heroes of the Soviet Union, one a Red Army general, the other a geologist who won the Stalin Prize, have been wiped from the Tashkent metro map. So have all traces of Vafery Chkalov, the test pilot who flew a Tupolev ANT-25 on the first non-stop jaunt from Moscow to Vancouver.

When Tsar Alexander II besieged Tashkent in 1865, looking to outfım the British for control of the approaches to Afghanistan and India, his army took over an Islamic walled city of mudbrick lanes, mosques and bazaars, built on the edge of a desert and depending on canals for its survival. Imperial Russia's first move was to build a fortress, now demolished, and then to create a new city immediately adjacent to old Tashkent, modelled as closely as possibie on Moscow. By 1906, when a railway finally connected Russia with its wild East through Tashkent, the city already had electric trams running in the streets, a palace for an exiled grandson of Tsar Nicholas I, and a Russian Orthodox cathedral built in the style of the 16th century. A state library opened in 1870, followed by an observatory, a museum and various schools. There are still traces of that world, with its classical mansions and its bandstands, reflecting a time when the two cities, Russian and Uzbek, lived entirely separate lives. Stalin had little time for the Tsars, but he did credit them with the creation of an empire that stretched from Finland to the Pacific, of which he was determined to keep control. Moscow's first step was to pour in the resources to make Soviet Tashkent more impressive than the imperial version of the city. During the Great Patriotic War,

as Russia describes the Second World War, the population of the city doubled as Soviet factories were evacuated to Tashkent to keep them safe from the invading Germans. The Soviets also embarked on their misconceived strategy of tampering with the flow of water into and out of the Aral Sea, which is partly in Uzbekistan. It brought water to Uzbek cotton fields, and helped make Tashkent green, but it has had disastrous long-term consequences for the region's ecology.

By the end of the war, Tashkent was the fourth-largest city in the USSR, and Stalin directed the building of appropriately elaborate new cultural institutions there. The grandest of them is the Alisher Navoi Opera House, designed by Alexey Shchusev, the Moscow architect responsible for Lenin's mausoleum and the KGB's HQ. Shchusev's design in Tashkent takes its place in an urban plan based on a network of boulevards fronted by Soviet classicism. The opera house forms one side of a formal square with an elaborate fountain framed by mature trees. It is a subtle and delicate exercise in classical architecture embellished with Uzbek architectural motifs, a world away from the oppressive nature of much architecture from the Stalin era.

Stalin’s successor, Khrushchev, denounced not only Stalin’s politics but also his architecture. Under his leadrship, Tashkent began to take on a more modern look, acquiring its ZUM department store and a new HQ for the Uzbek Communist party. But Tahskent’s most ambitious construction came later, triggered on the morning of 26 April 1966, when the city was hit by an earthquake.

By most definitions, an earthquake measuring 5.1 on the Richter scale would be defined not worst than moderate. The official death toll was a relatively modest 15. Yet the Tashkent earthquake was declared a catastrophe. Leoind Brezhnev, newly appointed general secretary of the Communist party, promised that the city would be rebuilt without delay. Whether it was an alibi for the political decision to remake Tashkent, or from genuine necessity, as many as 300,000 people were declared homeless and reported 80 per cent of the city was demolished. It was a chance for Brezhnev to establish a reputation for dynamic leadership - one that he lost as he declined into senility in the closing days of the Cold War. By rebuilding Tashkent as the model for a progressive Soviet city in Asia he could show the non-aligned world a seductive alternative to capitalism. At the same time he could secure the loyality if the Uzbeks while attempting to break the influence the Islamic clergy still had on the way of life in the old city by moving large numbers of people away from the mosques. The underlying idea was to integrate the Russian and the Uzbek cities, and to make them the core for a larger and more modern Tashkent.

Tashkent got a new university, government district, television tower, theatre, central post office and railway station as well as a cinema, sports palace and puppet theatre; the aircraft factory workers even got their own palace of culture. A great deal of new housing was also built, much of it in the form of ten-storey prefabricated concrete slabs, distinguished by a fondness for large-scale ceramic murals, and geometric sun screens. Architecturally, there was a range of styles; sober Soviet modernism, such as defined by the government centre, mixed with attempts at more fashionable versions of contemporary architecture clearly influenced by the architectural magazines that had begun publishing the works of Western architects such as James Stirling. In between was a streak of crowd-pleasing populism, with the ceramic-tiled domes of the Tashkent Circus and Chorsu Bazaar. Most intriguing was Andrey Kosinskiy and Georgy Grigoryants’ national bathhouse, in a style that was neither modern nor populist, but which looks like a modernised version of the old Islamic Tashkent, and might well have been inspired by the desert settlement in the first Star Wars.

Tashkent today is a city in a country waking up from decades of isolation, with visa-free travel and as accomodating a government as it has ever had. The isolation has inoculated it from the impact of mass tourism. Even if corruption and an authoritarian system are fuelling the bulldozing of some neighborhoods, it still has green parks and bandstands, cafés and ice cream parlours that are engaging reminders of the apparent innocence of the pre-capitalistic civic life. Open-air markets sell execrable oil paintings, samovars and Red Army relics from the pavement. None of this is likely to change in the near future, but unless Tashkent learns to value each of its previous incarnations as a city, it will lose its unique qualities.